According to the Chinese War Ministry, since the fall of

Rangoon, from May 1942 through September 1944, 98 percent of U.S. military aid

over the Hump had gone to the 14th Air Force—and, the ministry could have

added, to the B-29 operation and the upkeep of the large and increasing number

of U.S. military personnel in China. The United States had provided the two

million or so men who were in the Chinese army but not in the X and Y forces a

total of 351 machine guns, 96 mountain cannon, 618 anti-tank rifles, 28 anti-tank

guns, and 50 million rounds of rifle ammunition. Of these items, only 60

cannon, 50 anti-tank rifles, and 30 million rounds of ammunition were provided

before the June 1944 battle of Changsha; the rest afterward. Further, the

War Department had decreed that the new Z Force of thirty Chinese divisions to

be retrained and armed by the United States (as the second group of the ninety

total divisions that Roosevelt had promised to support) would receive only 10

percent of the total Lend-Lease allotment for China. The American team assigned

to this project calculated that if divided between thirty new divisions, these

supplies of arms and ammunition would in each case amount to “practically zero.

In early June, Stilwell was back in Chungking and discussed

the military crisis with Chiang and later in Kunming with Chennault. Both

repeated their earlier requests for a B-29 raid on Japanese depots at Wuhan.

Stilwell promised to forward them to Washington, but when the department

replied in the negative, he sent back a brief acknowledgment to Washington:

“Instructions understood and exactly what I had hoped for. Pressure from the

Generalissimo compelled me to send the request.” After his meeting with

Chennault, Stilwell also stuffed into his pocket and then promptly forgot

Chennault’s request that the two hundred fighters of the 14th Air Force

assigned to protect the B-29s be deployed against the looming offensive in East

China.

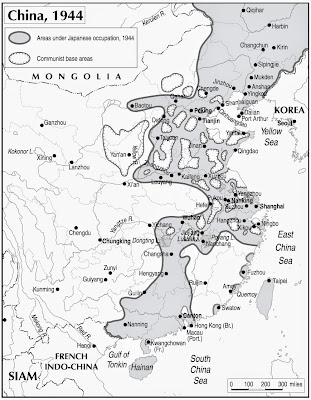

According to Stilwell, on June 5 in Chungking Chiang told

him “the situation in East China” (the expected offensive into Hunan) was to be

solved by air attacks and asked him to “suspend shipment of arms and ammunition

over the Hump” in order to concentrate on shipment of fuel, parts, and ordnance

to the 14th Air Force. Stilwell promised Chiang that he would assure that the

14th Air Force received 10,000 tons a month in supplies but he also seemed to

interpret Chiang’s instructions as an order not to use U.S. transport to

deliver from any location arms and ammunition to any of Chiang’s armies

resisting the Japanese in East China. It is doubtful that Chiang was as

categorical as Stilwell recounts in suggesting air power alone would “solve the

situation,” and Stilwell himself does not quote him as saying no American or

Chinese arms and ammunition should be sent to Chinese forces in East China. In

his diary, Chiang simply reports that he and Stilwell “discussed fuel supply

and weapons distribution” and Stilwell “politely promised to do as I wished.

His attitude was the same.” Actually only a “trickle” of American arms had been

going to Chinese forces not related to the Burma campaign, but Chiang believed

he had a compelling reason to control and even to stop any future American arms

from going to his commanders in East China. At that moment Xue Yue, commander

of the Ninth War Zone in Hunan, and General Zhang Fakui, commander of the

Fourth War Zone in Guangdong and Guangxi, had come under increased suspicion of

disloyalty— reports about which Stilwell’s headquarters believed were true.

By apparently directing at least that shipments over the

Hump be entirely devoted to supplies for the 14th Air Force and failing to

insist that the Americans send arms and ammunition to the Chinese forces in

Hunan—especially the threatened cities of Changsha and Hengyang—Chiang showed

that concern over disloyalty among his generals was more important to him than

the successful defense of these cities. As vividly expressed in his diaries, he

had enormous political and military interest in defeating the Japanese in these

looming battles—he knew the outcome would have a great effect on American and

domestic support for him. Thus he would take strong measures to try to defeat

the Japanese in Hunan, but, fearing supplies would fall into the hands of Xue Yue,

he apparently would not ask the 14th Air Force to drop even Chinese-made

ammunition and weapons to the defenders, nor did he discuss the air-supply

issue with Chennault.

Chennault was outraged with Chiang for not aiding Xue, but

he did not raise the matter with him, apparently assuming the effort would be

futile. But if Stilwell, who never hesitated to oppose Chiang’s decisions, had

had any question about the wisdom of Chiang’s orders as he interpreted them, he

could have sought clarification, or urged him to reconsider. This would have

been useful at least for the record. But Stilwell, like Chiang, had his own

potent political motives in these decisions. As will be seen, over the next two

months he clearly preferred that Chiang suffer a serious defeat in Changsha and

elsewhere in East China in order to enhance his own prospects of taking over

command of the entire Chinese Army. Chiang and Stilwell would both bear some

responsibility for the coming fall of Changsha and Hengyang. Perhaps because of

this, in his diary Chiang would not later blame Stilwell for these specific

defeats.

Xue Yue’s headquarters was some distance away from Changsha

and as the Japanese tightened their noose around the city, Chiang concentrated

on helping and directing General Zhang Deneng, whose Fourth Army comprised the

defenders. Chiang continued to press for increased logistical support of the

14th Air Force’s attacks on the Japanese attackers and lines of supply and he

ordered six armies from four war zones to deploy immediately to Hunan. When it

became clear that these units would arrive too late and Changsha would fall,

General Zhang, on June 26, without orders evacuated the city with 4,000 of his

men and trucks reputedly filled with his personal effects. Chiang had him shot,

although he was one of his favorite generals. The Japanese occupied what

remained of the wasteland of the city that had avoided its fate for so long.

Most of the population had long fled, including the American and Chinese staff

of the Xiangya Hospital. The loss of Changsha exposed Hengyang and Guilin to

the south and to the northwest, Chungking. Stilwell’s headquarters in the

provisional capital began planning for evacuation. Roosevelt quickly dispatched

Vice President Henry Wallace to China to “calm” Chiang Kai-shek and promote

cooperation between the Kuomintang and the Communists.

At this time came the almost simultaneous news of the

attempt on the life of Hitler and the resignation of the Tojo cabinet in Japan.

Tokyo’s surrender, Chiang thought, would “not be long” in coming. He believed

that if he could avoid a break with the Americans by temporarily giving

Stilwell command with some controls, the crisis with America would pass and

after the war the aggressiveness of the Russian and Chinese Communists would

eventually push the United States into opposing them.

But immediately Chiang was to start down the path toward

another defeat that would strengthen Stilwell’s hand and perhaps encourage his

warlord opponents. Having lost Changsha, victory in Hengyang, a hundred miles

due south of Changsha, would, Chiang felt, be “Heaven’s blessings” and would

“dissolve the diplomatic crisis and deliver us to safety.” The idea that the Nationalist

Army was about to collapse would be eliminated by such a victory. Again, Chiang

did not want to support Xue Yue, the war zone commander involved—so instead, as

at Changsha, he directly conducted the defense of Hengyang with loyal forces in

the city and elsewhere, which added to the chaos. But this time he had a

general, Fang Xianjue, who was willing to fight.

In his mission to save the city, Chiang relied heavily on

Chennault’s close air support. The tactic worked well at first. For a period in

early July, fighters and bombers of the 14th Air Force so disrupted Japanese

supply lines that the attack on the walled city ground to a halt. Then for one

week, lack of fuel grounded the American pilots. In accordance with Stilwell’s

wishes, the War Department still refused to allow Chennault to use aviation

fuel from the B-29 depot in Chengdu.

Meanwhile, on the ground, Fang repulsed three waves of

Japanese assaults on Hengyang, reportedly killing 7,602 Japanese soldiers. But

he lost most of his regulars—19,380 men—and by mid-July mostly auxiliaries and

service troops were in the front lines. Resupply became a critical issue.

Chiang again did not fly or parachute in supplies, and Chennault, without

telling Chiang, again requested that Stilwell authorize a single air drop of

ammunition (presumably Chinese manufactured), in this case at Hengyang.

Stilwell refused, saying he was concerned this would set a precedent for

further demands that could not be met. On July 20, Stilwell’s new chief of

staff in Chungking, General Tom Hearn, suggested authorizing Chennault to drop

a “token” of two hundred tons of ammunition into the city, but Stilwell in his

reply recalled with satisfaction what he said was Chennault’s old promise “to

beat the Japs with air alone.” In fact, neither Chennault nor Chiang had ever

claimed they could beat the Japanese without the Chinese Army playing a key defensive

role. But Stilwell went on to tell Hearn that if Chennault “now realizes he

cannot do [this], he should inform the Gissimo, who can then make any

proposition he sees fit.” This part of the message was inadvertently not passed

to Chennault by Stilwell’s staff. But in a segment of the same message that did

make it to Chennault, Stilwell, turning aside a request for supplies for

Hengyang from Bai Chongxi and clearly thinking of his own imminent takeover of

the Chinese Army, grumbled, “I do not see how we can move until a certain big

decision is made.” He added sarcastically: “You can tell the Chinese we are

doing our best to carry out the plan the Gissimo insisted on.”

In reply to Stilwell, General Hearn indicated that he was

aware of “the pending big decision” (Stilwell’s new appointment), but he

recommended that in the meanwhile “drastic action” be taken “immediately” to

aid the Chinese in southeast China. Chennault had offered to convert one

thousand tons of his Hump quota to arms and ammunition for the besieged forces

with or without Chiang Kai-shek’s approval. Stilwell turned down these

proposals as well as additional pleas for supplies from Xue Yue and Bai. In yet

another clear reference to U.S. pressure on Chiang for his command of the

Chinese Army, Stilwell told Hearn: “The time for half-way measures has passed.

Any more free gifts such as this will surely delay the major decision and play

into the hands of the gang. The cards have been put on the table and the answer

has not been given. Until it is given let them stew.” The meaning was apparent.

Hearn informed Chennault that Stilwell agreed that in order to restore the

situation in the east, a “real operation” was required, but “he is working on a

proposition which might give this spot a real face-lifting and is loath to

commit himself to any definite line of action right now. Consequently, we must

hold off in making any proffers of help to the ground troops until things

precipitate a bit more.”

Bai Chongxi once again urged Chiang to pull back from a

besieged city, in this case Hengyang, and concentrate on attacking the enemy’s

lines of communications. But Chiang still thought it was necessary to show the

Chinese people as well as the Americans that the Chinese military was fighting

the enemy head on and could win. Still, as at Changsha, the imperative to win

at Hengyang was not strong enough to compel Chiang to insist that ammunition

and other supplies be flown to the defenders. Chiang told General Fang inside

Hengyang to keep fighting and ordered nearby armies to try to relieve the city.

Stilwell’s U.S. Army observers reported that the 62nd, 69th, and 37th armies

did in fact take heavy casualties trying to break through the Japanese forces

surrounding the city, while three other armies also suffered severe losses

while attacking Japanese supply lines. Henyang was finally secured by the

Chinese on August 1. After the war, the government built a memorial of 5,000

skulls collected from unburied Chinese soldiers. The Chinese armies were not

winning, but no one could say they were not fighting.

No comments:

Post a Comment